Nurture Your Life Force

By: Amy J. Hughes, Ph.D., Corning Museum of Glass, USA

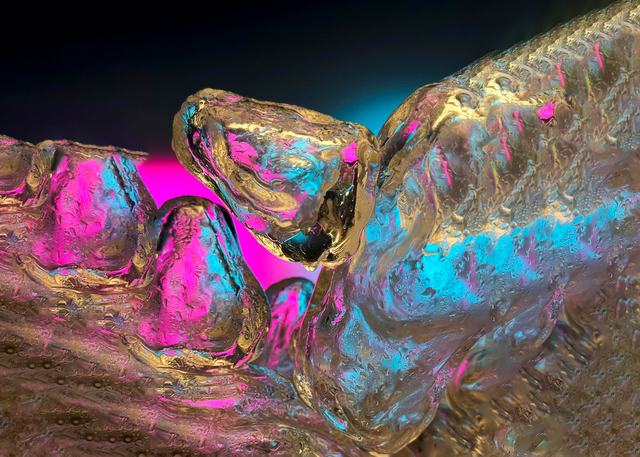

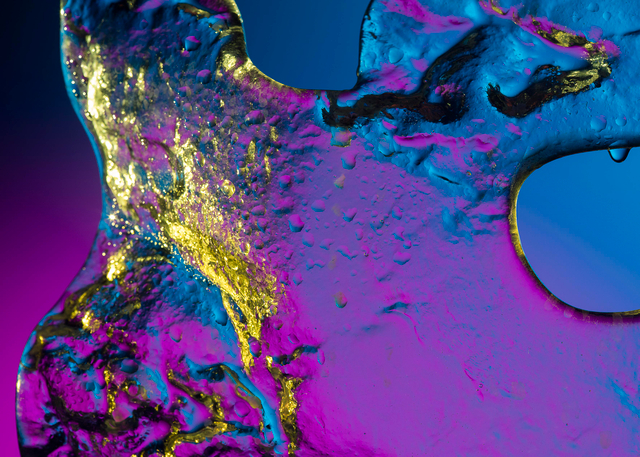

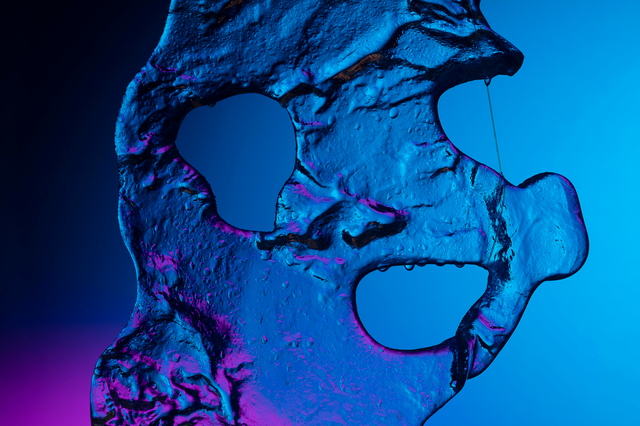

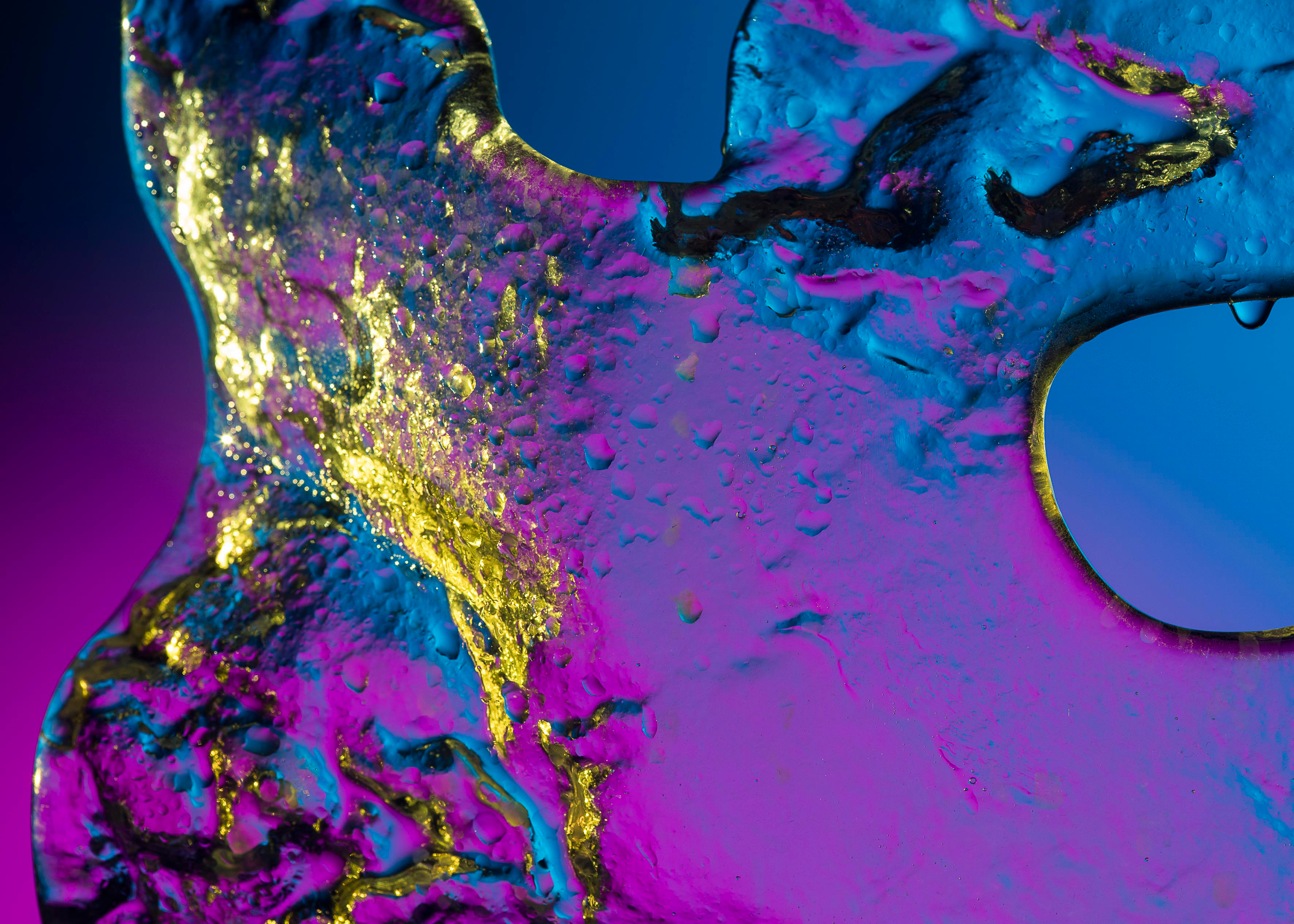

Photo: Jiří Thýn and Estate of Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtová (River of Life, courtesy of Jaroslav Zahradník)

As a curator and visual cultural historian, I find it striking how depictions of water in art often embody a source of inner fuel, nourishment and strength, particularly against backdrops of great political and cultural turmoil, upheaval and injustice. Stanislav Libenský (1921–2002) and Jaroslava Brychtová’s (1924–2020) Řeka života (River of Life), 1968–1970, displayed at the 1970 World Expo in Osaka, Japan, embodies a sense of glass as a profound foundation of life—not just a source of life in a biological sense but a source of a duchovní, an inner life force. There is no English equivalent for duchovní. The word derives from the root duch, usually translated into the English noun ‘spirit;’ duchovní as the adjective ‘spiritual.’ Spiritual is closely associated with religion, and although duchovní can be linked to a religious meaning, it holds much broader connotations connected to concepts of intellect and psychology, a sense of culture, general state of mind, and currents of thought. A duchovní life force conjures this sense of an inner/soulful personal or cultural current of an intellectual/psychological/mindful life force.

Spanning 22 meters, reaching 4.5 meters high and weighing 12 tons, River of Life consisted of clear, vertical, double-layered glass panels hung on horizontal steel supports. (Jaromíra Maršíková, “Expo 70.” Revue du Verre 3 (1970): 66) It mimicked the natural trajectory of a stream originating high in the mountains softly cascading downward. The first panels were high enough so an average-height adult could walk underneath. The supports decreased incrementally in height, bringing the panels closer to the ground as the work moved through space. The panels showcased negative casting in a series of abstract spheres, cylinders, and diagonal lines. Some displayed life-size casts of female figures swimming and imprints of bare feet dancing, symbolizing “various amusements [that] take place by the river.” (Jaroslava Brychtová, interview, Expo po česku. Období triumfů. Česká televize, 2015. I thank art historian Mgr. Petr Šámal, PhD for translating assistance; Jaroslava Brychtová, interview with author, Železný Brod, Czechia, July 26, 2018)

On the sculpture’s exterior were engraved army boots, overt references to the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia led by the Soviet Union. The boot prints represented death, and as the panels cascaded downward, the once flowing, orderly forms grew more chaotic, signifying the freezing of the river. (Brychtová, interview with author, July 26, 2018)

The work radiates the type of deep, universal duchovní life force striving for expression and realization. The generative, soul-fueling, and healthy-in-body-and-mind “amusements” River of Life depicts— swimming, dancing, relaxing—are types of activities we need to regenerate, center, and nurture ourselves in deep, creative ways. These amusements are not frivolous—they are serious, since they remind us that the freedom to play, create, and relax are critical to our overall well-being. Tending to our self-care helps us be our best selves for our loved ones, colleagues, and fellow citizens.

The boots represent the assault on these freedoms. Brychtová told me they wanted to make “the biggest statement possible” against the invasion. (Brychtová, interview with author, July 26, 2018.) The artists followed their artistic and personal impulses to convey feelings in a climate that prohibited such expressions and often imposed political consequences for expressing discontent with the regime. In this sense, River of Life expressed their truths about a moment in time they experienced. Speaking one’s mind, even briefly and imperfectly, and acting in alignment with one’s beliefs is a way to nurture our duchovní life force, stay connected to it, and feed it what it needs to build resiliency and inner strength.

Against this backdrop of the political climate, it is no accident that water and the personification of a river were an inspiration for this sculpture. The ability of large bodies of water to change appearance, absorb violent tempests, persevere and remain intact are visual reminders for us to be grounded in ourselves, trust that we can weather the storms of life, and remember that while storms may leave us battered, scarred, and even forever altered, we can persevere. Unbridled power and aggression—human or aquatic—can destroy and leave life forever changed. But forms of life ultimately return. River of Life’s message was muted (the boots were ground out before the fair’s opening), and it was broken, cut up and remains largely obscured to this day, but its duchovní life force still resonates in its message of fortifying and strengthening our inner soul center and modeling resiliency in the face of adversity.

The world needs more Rivers of Life, particularly in public spaces. In the face of increasing repressive forms of authoritarian, fascist, and anti-Semite movements throughout the world, we need visual reminders of the rivers of strength and resiliency within us to confront the challenges of our time. River of Life reminds us of the critical importance of caring for our individual and collective humanity and standing up to the powers seeking to dehumanize and oppress. We must strengthen our own duchovní inner life force and speak up, speak out, and get involved as we build our inner resiliency and personal and social practices of care for ourselves and those around us amidst the urgent issues facing our world today.

Amy J. Hughes

Ph.D., is Assistant Curator at the Corning Glass Museum specializing in 20th-century Central European art, design and visual culture with a focus on affect as political strategy in monumental public glass sculpture and photography in postwar Czechoslovakia. She has held positions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Institute of Art History at the Czech Academy of Sciences, and has taught extensively on art and glass history in classes in the U.S, France and Czechia.

Jiří Thýn

He is considered a leading Czech post-conceptual photographer of the middle generation. He explores the photographic medium in relation to other artistic fields: object, installation, moving image, poetry, drawing or painting. He has headed several photography studios at Czech universities: the FAMU, UJEP and currently leads the photography studio at AAAD together with Václav Kopecký. He is represented by the Prague gallery hunt kastner based in Czechia.