Tactile Touch

By: Emma Hanzlíková

Photo: Richard Bakeš, archive

In the distant past, a French abbot and historian, Suger of Saint-Denis, perceived glass and light as existing in a symbiosis of beauty. He formulated a theory based on the idea of cathedrals being defined by beauty, and the way he conceived his 12th-century reconstruction of the Basilica of Saint-Denis made the building go down in art history as one of the first examples of the “dematerialized” Gothic-style architecture for which, among other things, stained-glass windows are typical. Daylight enters the cathedral through stained-glass windows, creating new patterns in the interior.

DIVINE REFRACTION INDEX

Light was not adored by abbot Suger alone, it was in fact one of the key aspects of medieval aesthetics in general. It was perceived as an embodiment of the metaphysical presence of God. For the last few centuries, religious worship, and perhaps even standard practice, have not been favourable to the creation of fundamentally innovative works of art within the established church tradition.

In spite of this, there are countless examples of unconventionally treated windows in European cathedrals, created by famous artists who were asked to use a window instead of a canvas. At the end of the 1940s, Henri Matisse designed the stained-glass windows for the New Chapel of Vence; twenty years later, Marc Chagall created the windows for the cathedrals in Reims and Metz, and a new stained glass-window decorated with colourful abstract patterns resembling pixels was designed in 2007 by Gerhard Richter for the cathedral in Cologne.

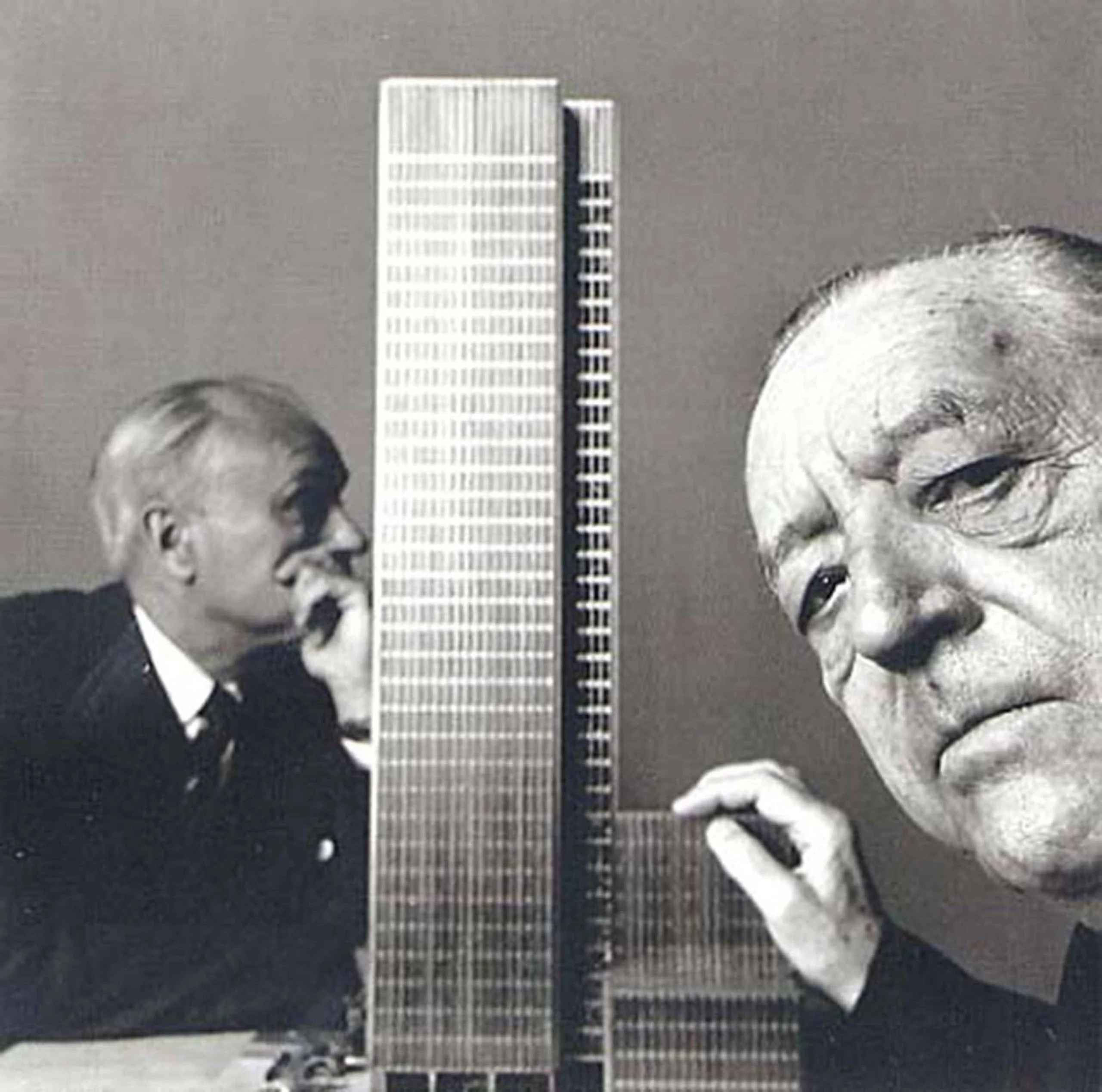

One of the first glass skyscrapers had a great impact on architects all around the world, among them Czech architect Karel Prager, who admitted to having drawn inspiration from this project. Although the first imitation of Seagram Building by Mies van der Rohe (1954–58) is often considered the Strojimport building (1962–72) by Zdeněk Kuna, Zdeněk Stupka and Olivier Honke-Houfek.

The most recent, and perhaps the most striking example of this technique, are the windows of the Grossmünster Cathedral in Zurich. Designed by Sigmar Polke, they are made up of transparent, thinly sliced pieces of agate. From folklore through censorship to new technologies In Czechoslovakia too, many modern painters participated in the decoration of churches. Among the most famous executions is the decoration carried out in St. Vitus Cathedral and completed in 1929, with stained glass windows by Mikoláš Aleš, František Kysela, Alfons Mucha, Karel Svolinský and Max Švabinský.

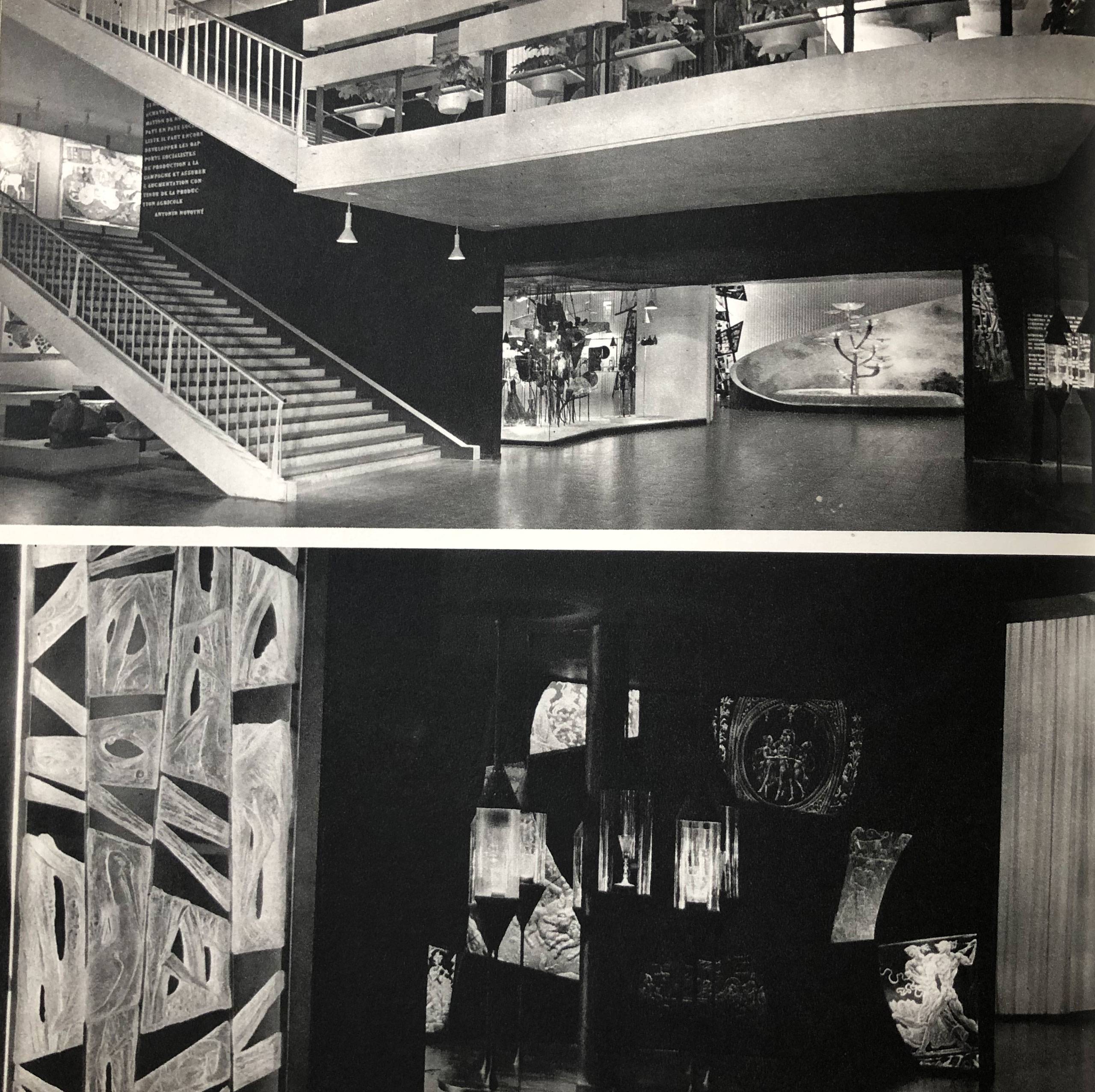

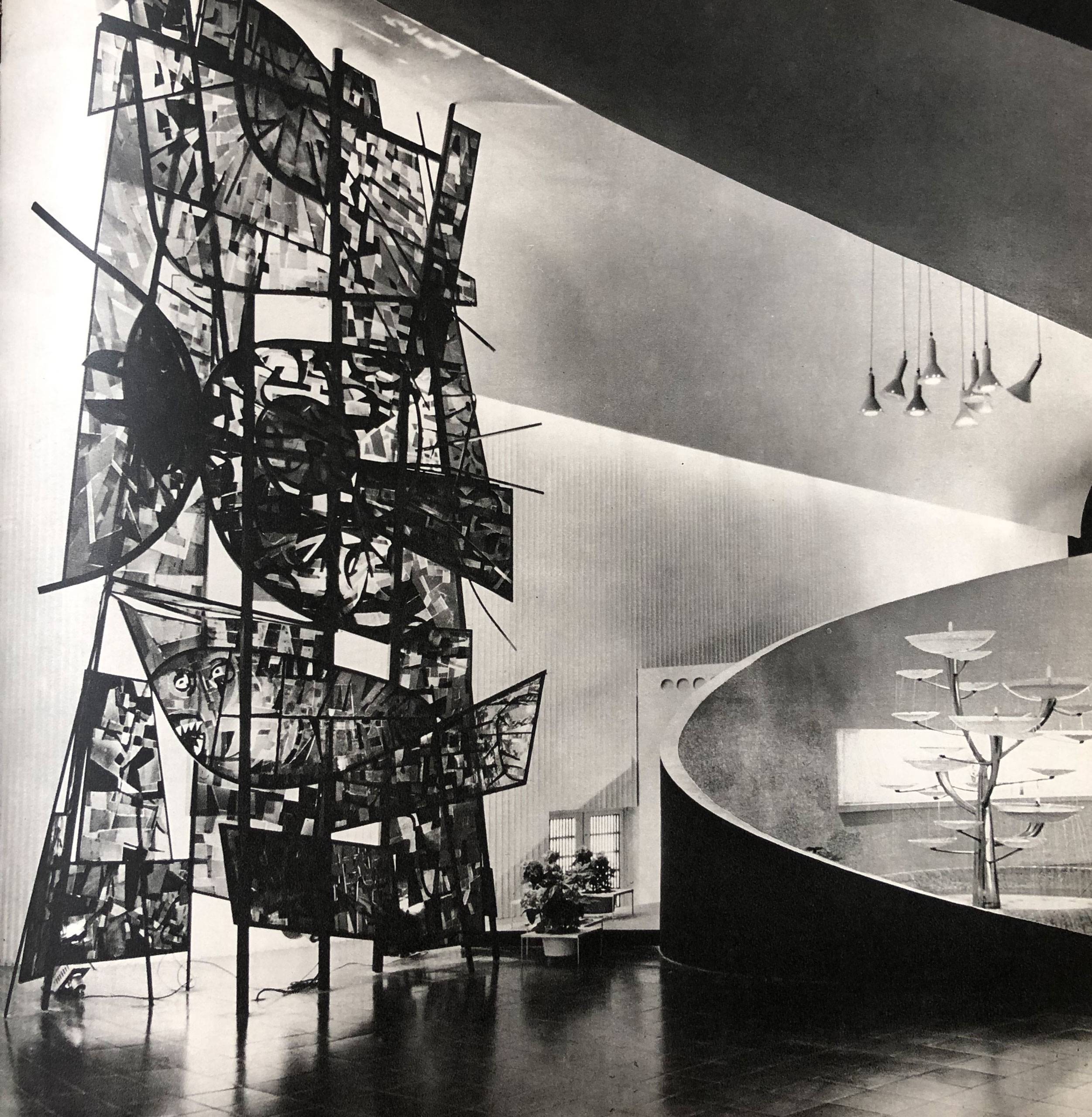

A decisive moment in the development of the stained-glass window technique, however, came with the event of the EXPO 58 World Exhibition in Brussels. In Czechoslovakia, the 1950s and 1960s were a period of the most intense experimentation with artistic stained glass and its monumentality, exemplified by the expressive three-dimensional stained-glass installation entitled Sun, Water, Air (1957–58), created by Jan Kotík for the Czechoslovak pavilion in Brussels.

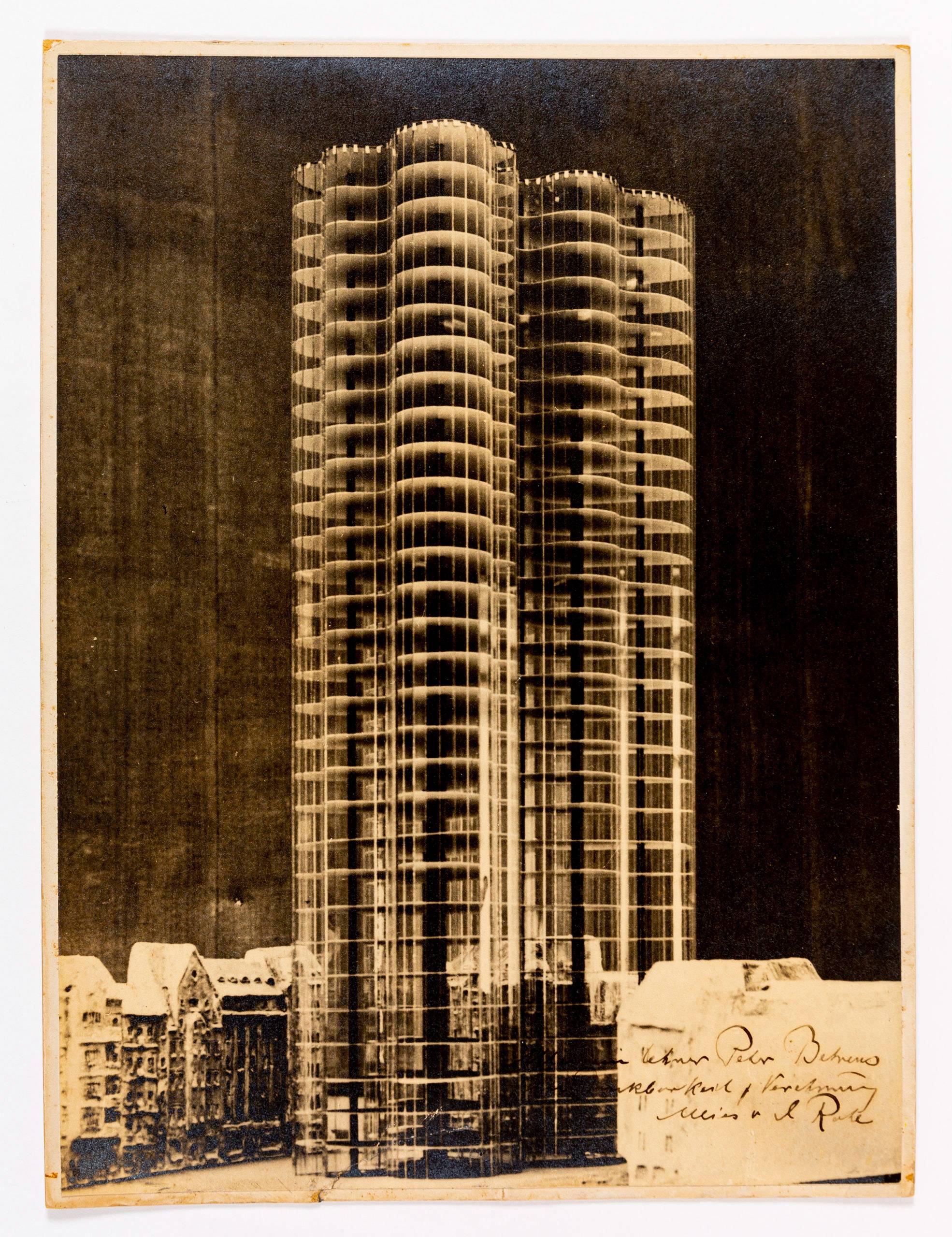

The model for a glass high-rise building for Berlin (1922) helped Mies van der Rohe understand that through employing glass in architecture it is possible to achieve the rich interplay of light reflections.

In many cases, the focus was no longer on the classic stained-glass technique used in cathedral windows consisting of handmade and hand-painted pieces of glass traditionally held together by strips of lead. Many entirely new technologies emerged from Josef Kaplický’s glassmaking studio at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague, such as the production of moulded and etched glass with reliefs that influenced the work of the next generation of glassmakers.

To some extent, a tradition established itself in Central Europe that was based on the 19th century folk glass underpainting from which numerous artists drew inspiration. It seems paradoxical that it was during the Communist regime when the production of stained glass flourished the most. Since glassmaking was perceived as a craft during the totalitarian regime, it was not subject to the socialist aesthetic doctrine.

Glass as a material allowed many artists to focus on abstract forms in order to create decorative elements for architecture, which were often other than religious. The government regulation at that time specified that one to four percent of the total construction budget had to be used for artistic decoration, making artists essential collaborators of the architects.

Regretfully, many fragile glass artworks from the period of normalization did not survive the 1990s and the incompetent approach to interior renovations. There were, however, some rare exceptions to this unfortunate rule, for instance the 1964 stained-glass object created by the Vála sisters for the interior of the entrance hall of the former Institute of Theoretical Foundations of Chemical Technology in Prague.

THE SPIRITUAL ESSENCE OF ART

The way glass artists approach the stained-glass windows is completely different than the approach of painters. Internationally respected artists Jaroslava Brychtová and her husband Stanislav Libenský had the ability to capture and highlight the spiritual essence of a place without necessarily relying on motifs from Christian iconography. In their works decorating sacred spaces, they managed to achieve a sense of the transcendental even during the period of uncompromising normalization. They created windows for several chapels, including two for St. Wenceslas Chapel in the St. Vitus Cathedral (1964–68).

The empty glass prism houses only one sacred object — the Junkers F 13 aircraft in which Tomáš Baťa, the entrepreneur and founder of Bata shoe company, died in 1932. The monumental but also very simple building by František Lydie Gahura (1933) is a modern reference to a subtile Gothic cathedrals with stained-glass windows. This functionalist gem successfully combines both religious and secular ambience.

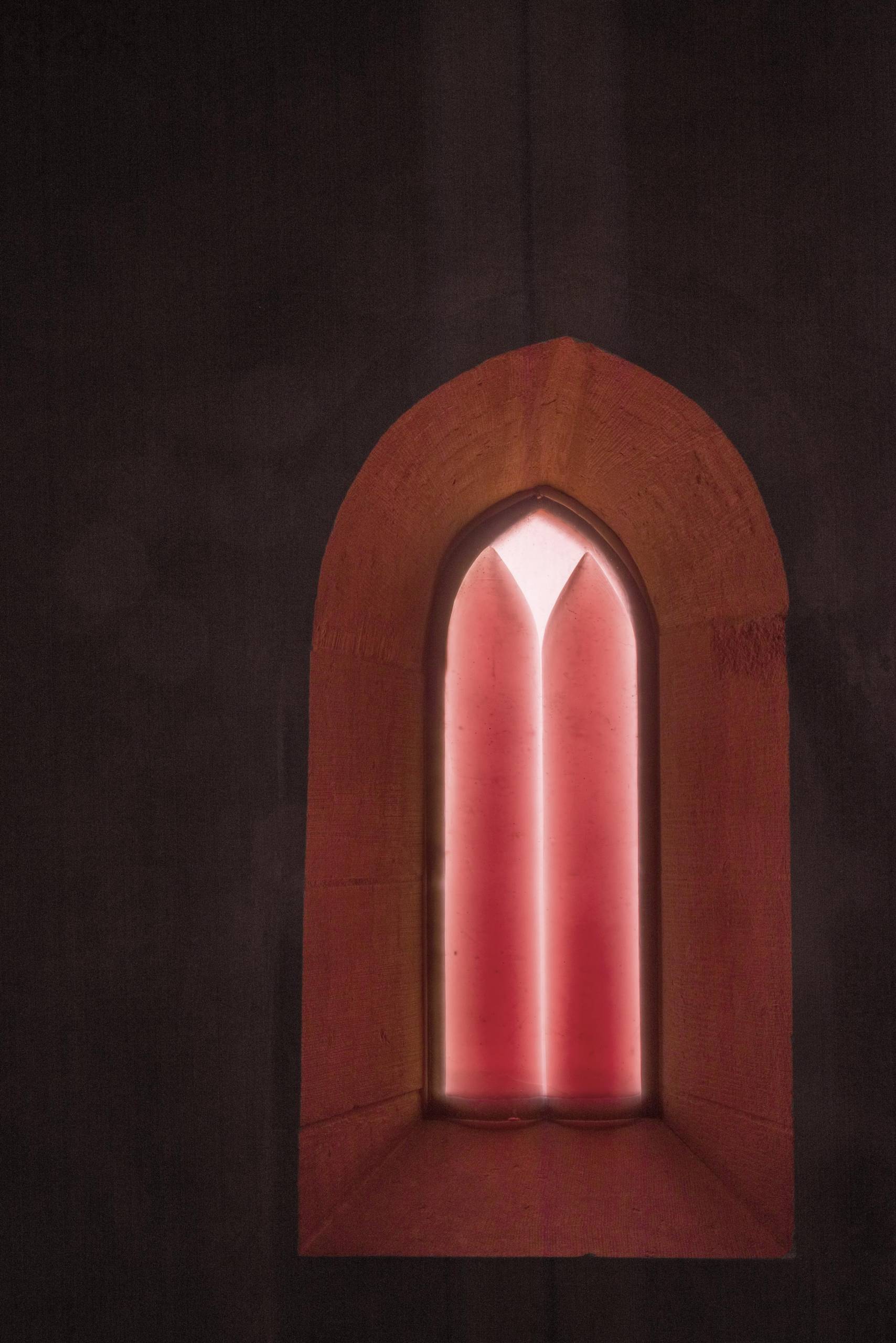

Particularly impressive is their glass decoration of the gate in the early Gothic chapel of the Most Holy Trinity of the Horšovský Týn chateau (1987–91). The window panes made from float glass have the capacity to accentuate the properties of the interior while remaining its integral part. Depending on the daylight throughout the day, the light passing through the tinted glass produces various kinds of atmospheric effects.

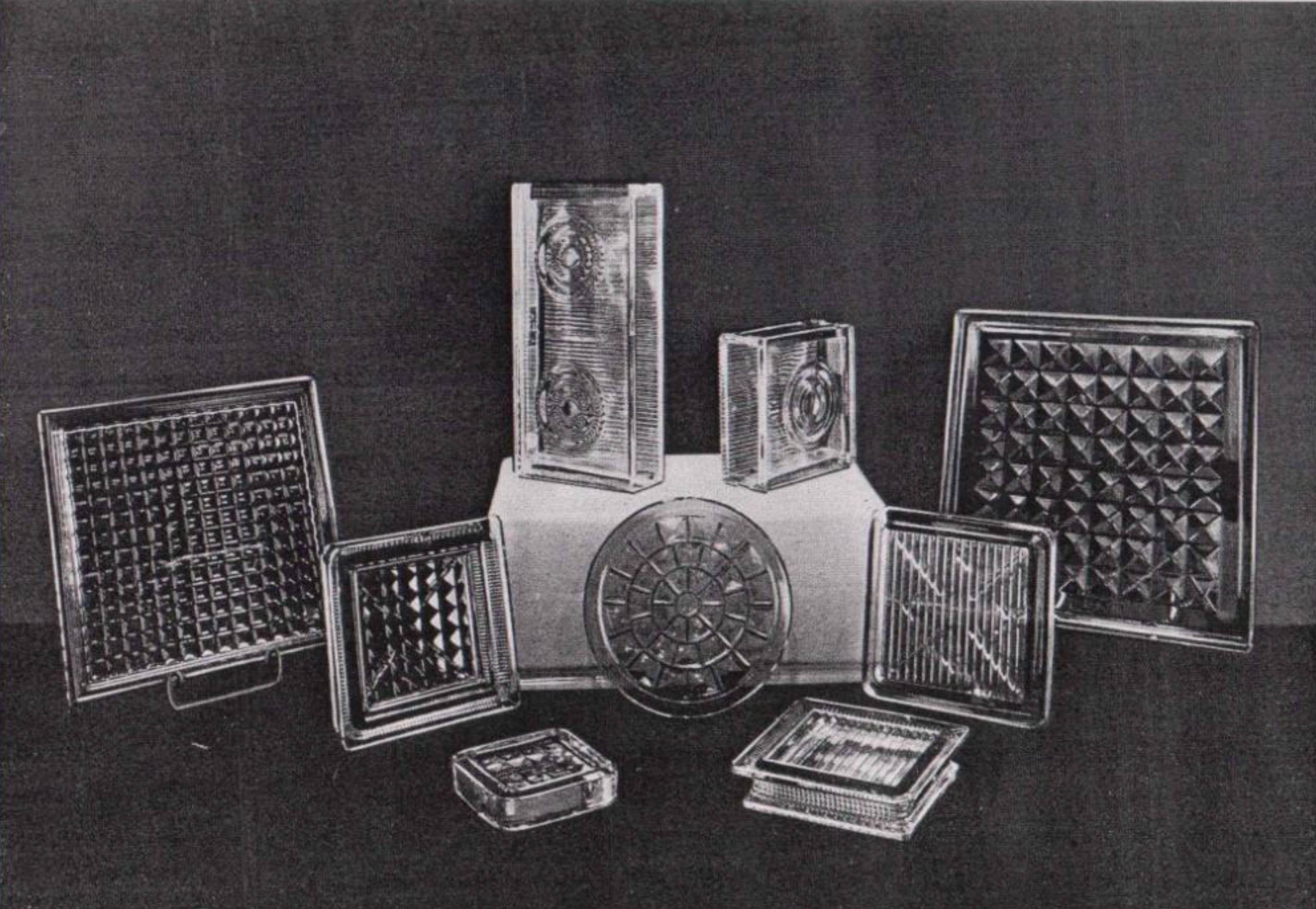

The ‘luxfery’ glass bricks of various shapes and patterns were both loved and hated. Modernist architects favoured the possibility of transparent walls but for many, especially residents from Eastern Europe, they have the after-taste of communist era when they were highly overused in interiors.

Brychtová and Libenský were not primarily concerned with the interpretation of the liturgy, but with the pursuit of their own artistic strategy whose aim was experimentation with glass and its exploration as a material. In order to understand the spiritual dimension of their works, it would perhaps be more adequate to acknowledge the influence of Zen Buddhism, which they observed in the principles o of the work of the Japanese architect Tadao Ando.

The International Exhibition EXPO 58 in Brussels was a legendary success for Czechoslovak glass. The exhibition One Day in Czechoslovakia won a Gold Star and thirteen other awards. The exhibition was designed by Jindřich Santar, who collaborated with Jiří Trnka, Antonín Kybal and leading glass artists Stanislav Libenský and Jan Kotík. Following great international recognition, the so-called Brussels style developed in architecture and design in Czechoslovakia in the following years.

FIAT LUX

Creating a completely transparent house has been the dream of many architects since time immemorial. Despite the fact that botanical greenhouses allowing the growth of tropical plants even in northern climates can be traced back to as early as the 17th century, it was not until 1851 that the greenhouse-like structures were used for an entirely different purpose, namely industrial exhibitions. The architect Joseph Paxton used his knowledge as a landscape gardener to build the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, for the first Great Exhibition.

This temple of consumerism with the ground plan of a traditional basilica, however, did not boast any stained-glass windows. The prefabricated cast-iron structure with glass panes allowed for easy assembly while also fulfilling the requirement for a temporary structure. The lifespan of this building that could, quite appositely, be described as the largest shop window of the world, was only six months, but since then glass has become a fixture in architecture, finding its way to its very foundations.

Horizontally divided sculptural stained-glass installation Sun, Water, Air by Jan Kotík exhibited during EXPO 58 in Brussels depicts the sun, a flying bird and swimming fish. These colourful images have a lot in common with the classical Gothic cathedral stained glasss windows, although their purpose was not religious but purely decorative.

The glass brick, known in some languages as the luxfera, or the light-bearing brick, emerged to become a prototypical, yet unconventional structural element across civilizations. Just thirty years after the London Great Exhibition ended, James G. Pennycuick had his invention of the glass brick patented in Boston. In Bohemia, the glass bricks were used for ceiling illumination in the construction of the Prague arcades in the Lucerna Palace or U Stýblů and glass blocks, specially designed by František Vízner in 1981, were also used for the facing of the line B stations of the Prague underground.

The connotation of being Lucifer’s curse has its roots in the rather abundant use of the glass bricks in the bathrooms of prefabricated blocks of flats of the normalization era. Nevertheless, the glass bricks of decorative shapes were used as early as 1902 by Dušan Jurkovič on the wall beside the spiral staircase of Jan’s house in Luhačovice, combining Art-Nouveau elements with traces of local folklore tradition.

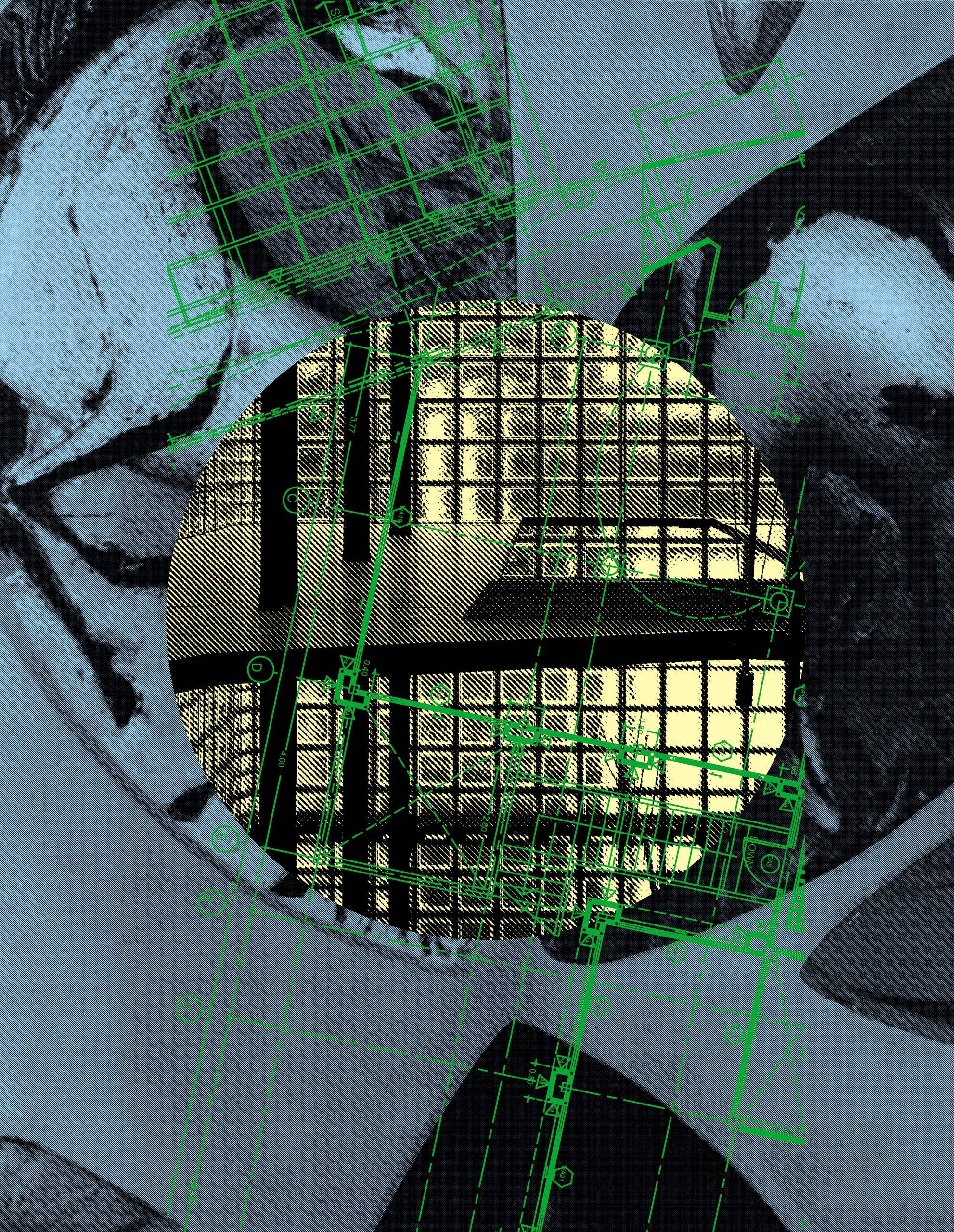

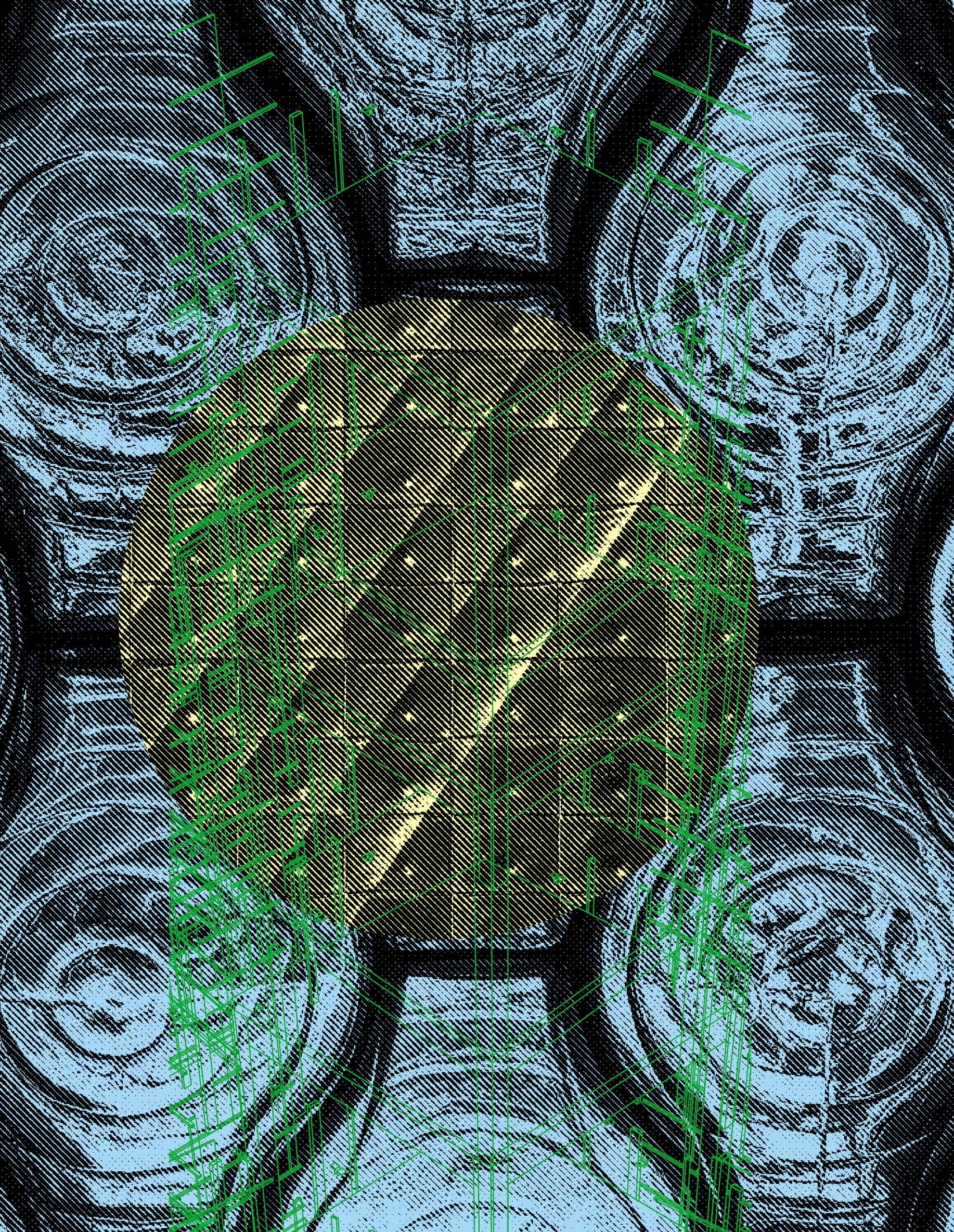

Stanislav Libenský photographed while working on a monumental study of windows for St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague (1964). He designed them with his life partner and collaborator Jaroslava Brychtová. The pair became world famous for their monumental glass sculptures, but also created the stained-glass windows in the Chapel of St. Wenceslas in Prague’s St. Vitus, Wenceslas, Vojtěch and Virgin Mary Cathedral (1964–1968), the window in the Chapel of St. Anne’s Chapel in St. George’s Monastery at Prague Castle (1974–1975), seven stained-glass windows for the castle chapel in Horšovský Týn (1987–1991) and eight windows for the castle chapel at Špilberk in Brno (2001–2003).

GLASS AS AN ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENT

However, the glass bricks do not have to be used only as a decorative accessory of architecture. Renzo Pian’s design for the Hermés department store on Tokyo’s Ginza (1998–2001) proves what counts. The very first glass building was erected in Paris. Designed by architects Pierre Chareau and Bernard Bijvoet, the late 1930s Maison de verre was to serve as a private gynaecologist’s office. At that time, the functionalist architects were already working with the notion of a completely lightweight skeleton structure and hung sash windows.

Around the same time, a thousand kilometres to the east of Paris, the architect Mies van der Rohe managed to design hung sash windows for the Villa Tugendhat (1929–30) in Brno. Sliding automatically into the floor, the windows disappeared, creating a sense of complete interconnection between the interior and the exterior. This can be perceived as an absolute fulfilment of the requirement of transparency, where the view of the garden is not disturbed in any way.

Libenský and Brychtová were able to achieve a sense of the transcendental only by monochrome glass and its texture. The distinctive colours of the glass in the Holy Trinity of the Horšovský Týn chateau, (1987–91) shaped in mould create an interesting play of colourful light in tones of grey, blue, pinkish-orange, purple and pink which in the early evening harmonize on the chapel walls with the coloured sandstone of the ribs.

The idea of a house built entirely of glass was something van der Rohe considered even earlier. In 1922, he designed a building known as the Glass Skyscraper for the city of Berlin. A model made of glass made him realize that “by employing glass, it is not an effect of light and shadow one wants to achieve, but a rich interplay of light reflections”.

After emigrating to the United States, he created a glass-clad house in New York. The Seagram Building (1954–58) was one of the first skyscrapers boasting an all-glass facade. A few floors lower, yet still very similar, is the building of the Institute of Macromolecular Chemistry of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences in Prague, designed by the architect Karel Prager (1958–60). Prager himself admitted to have embraced the legacy of Mies van der Rohe.

Architect Prager liked to work with metal and glass and could not imagine modern architecture without these materials. For him, glass symbolized the modernity of tomorrow, as he himself stated: “The vision of modern architecture has always been linked to glass as a fundamental artistic and structural element”.

On several occasions, Prager asked the aforementioned couple of glass artists to collaborate on his projects. As for “glass in architecture”, the work of Brychtová and Libenský easily covers all the categories imaginable. In addition to free-standing interior sculptures, they were capable of producing sacral windows, wall-mounted reliefs, fountains, columns, or even covering an entire building in glass, as in the case of The New Stage of the National Theatre (1981–83). In collaboration with the building’s architect, Karel Prager, they created a glass facade made of hollow blown SIMAX resembling television screens or glass bricks on steroids.

Karel Prager cooperated with Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtová on the exterior of The New Stage of the National Theatre in Prague (1981- 83). As per the vision of modern architecture he manifested: “Clarity and brilliance, shimmering elegance, subtlety and softness of reflection, cold magnificence and colourful exuberance, sense of permanence and durability, matter-of-factness and reality, transparency and crystalline purity as well as delicacy, pride and grandeur are the emotive features which underpin the imaginative qualities of the style of future decades, and which are rendered concrete by the perception and effects of glass surfaces in architecture.”

HOUSE MADE OF BOHEMIAN GLASS

Designed by the ov‑a architectural studio and completed four years ago, the headquarters of the Lasvit company have become the present-day Crystal Palace as well as a tribute to all the buildings in Czechia that were made of glass. Overlapping glass tiles, developed in collaboration with Lasvit and its glass and technology experts, are inspired by the way slate roofs are laid. As a result, the glass facade is accentuated by an unusual, scale-like effect. An interesting monument to Tomáš Baťa was designed in 1933 by architect František Lýdie Gahura. Situated in Zlín, it has a distinctive but intangible quality of being just on the borderline of the sacred and the profane. Its most prominent feature is a delicate glass exterior.

Lasvit HQ in Nový Bor by Czech studio ov‑a (2019) is an hommage to the glass houses which became an independent motif in the history of architecture. The delicate cottage giving the impression of an igloo built of ice blocks, in facts embodies the glassmaking tradition of the region of the northern Bohemia region.

Perhaps it is the muted, diffused, coloured or otherwise distorted light passing through glass that astonishes us. And Czech artists and architects have proven on numerous occasions that it is not necessary to get a commission to produce sacral works to be able to convey the mystical moment of enlightenment.