Your Privacy

By: Emma Hanzlíková

Photo: Lenka Glisníková, Getty images, archive

Accept All Cookies Or Build A Firewall

Despite being perceived by our senses, architecture copies traditional paths trodden for centuries. Woman stays in the house, she inhabits the interior whilst the man comes out to the exterior, looks from the outside and comes back home. In 1975, Laura Mulvey opened the discussion about the stereotypical male gaze in her film essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Almost twenty years later, however, the renowned Spanish theorist Beatriz Colomina studied the gaze inside architecture.

The collage blends three models of Lasvit Art Walls – Curtain, Impasto and Tapestry. All of them serve to separate the interior and help to create an impression of privacy.

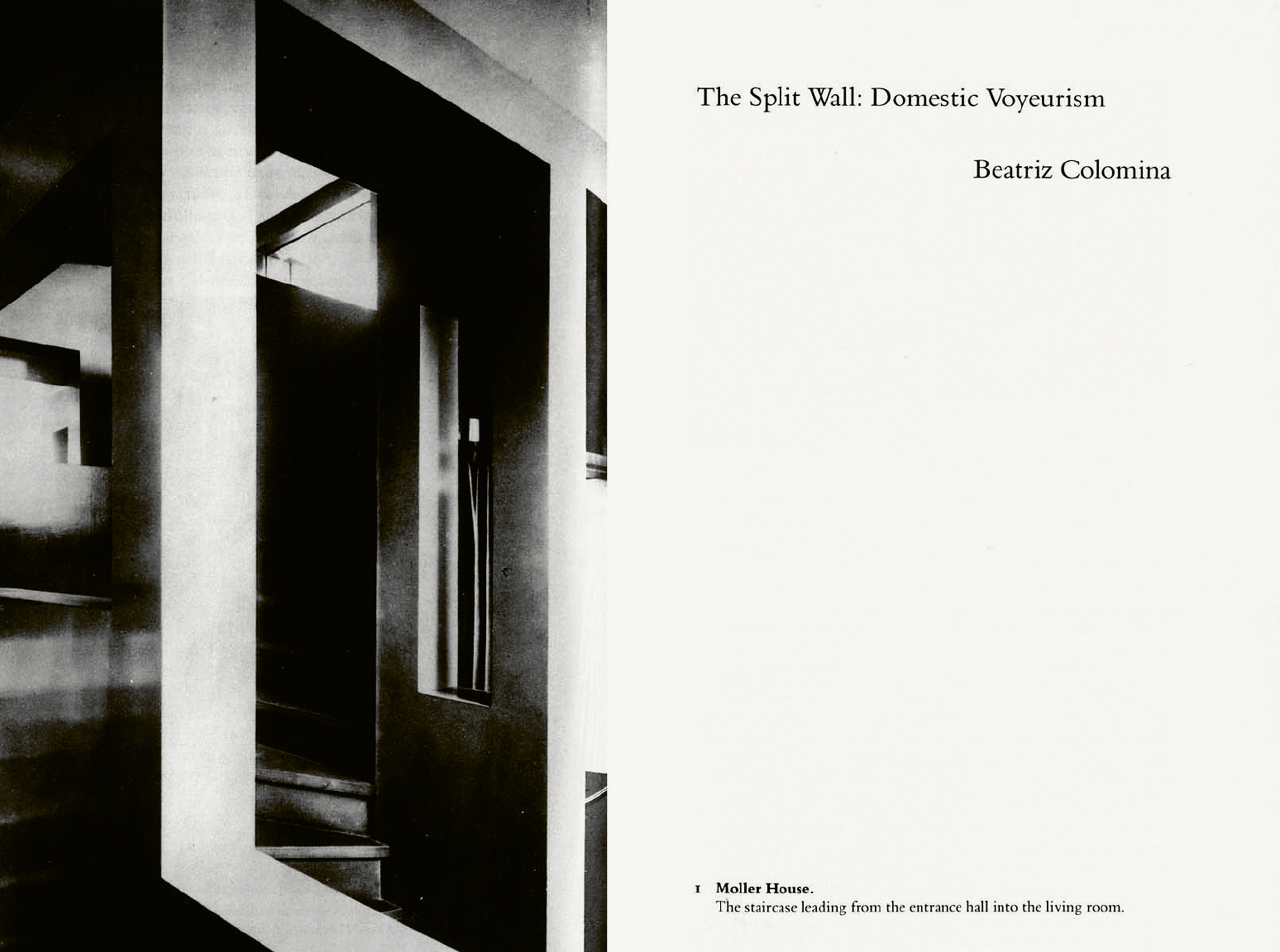

In her paper The Split Wall: Domestic Voyerism, she points out, inter alia, the theatrical aspect that is inextricably linked with interiors made by the infamous modernist architect Adolf Loos. This aspect is the most remarkable in such interiors where Loos inserts a theatre box – a space meant for the lady of the house. Thanks to a Raumplan she can sit at the heart of the house quietly and out of sight. Such an intimate space, which can be found also inside the Vila Müller in Prague (built between 1928 and 1930), enables the owner to control who is about to enter or leave her private space. And suddenly the chased object becomes the hunter.

The iconic scene from The Graduate movie by director Mike Nichols was also transcribed on the poster. Student Benjamin watches his parents‘ older friend Mrs. Robinson putting on his stockings. However, the scene is dominated only by a fragment of the female body and Benjamin‘s male voyeuristic view.

As was proved by Adolf Loos, surveillance is possible without any punishment. On the other hand, the concept of the prison panopticon by the British philosopher and social reformer Jeremy Bentham from the end of the 18th century might be regarded as the total opposite and complete withdrawal of privacy, where nothing is hidden from a guard’s sight. Yet prison and/or monk cells serve the functional purpose of a simple split wall creating a certain illusion of privacy á la chambre séparée. Split wall as studied by Beatriz Colomina is a historically important architectural element for creating a division. Zone demarcation designated for strictly private use does not have to be a permanent construction from reinforced concrete.

The scenography of Loos‘s interiors, which also includes Prague‘s Muller Villa, is followed by theorist Beatriz Colomina from the point of view of female residents. In the text The Split Wall describes the lady’s room: “Zimmer der damme — suspended in the middle of the house, this space assumes both the character of a “sacred” space and of a point of control. Comfort is paradoxically produced by two seemingly opposing conditions, intimacy and control.”

Already Gottfried Semper started to notice the transferable rugs used by nomadic people to replace walls, and also primitive nations working with woven walls from grass. Its woven grid refers to the sight of the inhabitant inside a private zone, who is able to oversee everything inside and at the same time, thanks to the back reflection, not be seen. Decorative wooden walls that become more like windows with laced Islamic ornament called mashrabiya can be found in Arab architecture since the Middle Ages and remained in modern variations up to this day. Despite their first use in Coptic sacred architecture they expanded to residential areas as well.

The person or object hidden behind the corrugated Liquidkristal wall, designed for Lasvit in 2012 by Ross Lovegrove, looks blurry. Its contours dissolve and remain unclear.

A similar approach to privacy can be found in the Asian island culture. Japanese architecture can be regarded at first as rather open, even functionalist. Yet thanks to its temporary structures it can create private corners in a second. Sliding paper screens and doors called shoji together with byōbu decorative panels can disguise spaces that are not meant to be seen. The beauty of shoji lies in the absence of stark division thanks to the misty transparency of light. Human bodies behind paper walls lack clear lines and shadow silhouettes create an erotic spark leaving much to our own imagination.

Originally from Ireland, designer Eileen Gray was able to combine rare materials with ordinary ones. Its room walls, inspired by Japanese aesthetics, stand on the border between sculpture, architecture and furniture. This four-piece screen from the 60‘s combines cork with light mahogany. But she also designed screens with a Japanese polished lacquer finish in contrast with metal.

Screens on the other hand can create a non-transparent division albeit only to a certain height. They became popular again during the pandemic. With conferences and meetings having to move online, screens started to appear frequently as zoom call backgrounds. The architect and designer Eileen Gray, for instance, was inspired by the Japanese aesthetics of screens as well as the technique of layered lacquer, and her walls move between being mobile sculptures and a piece of furniture.

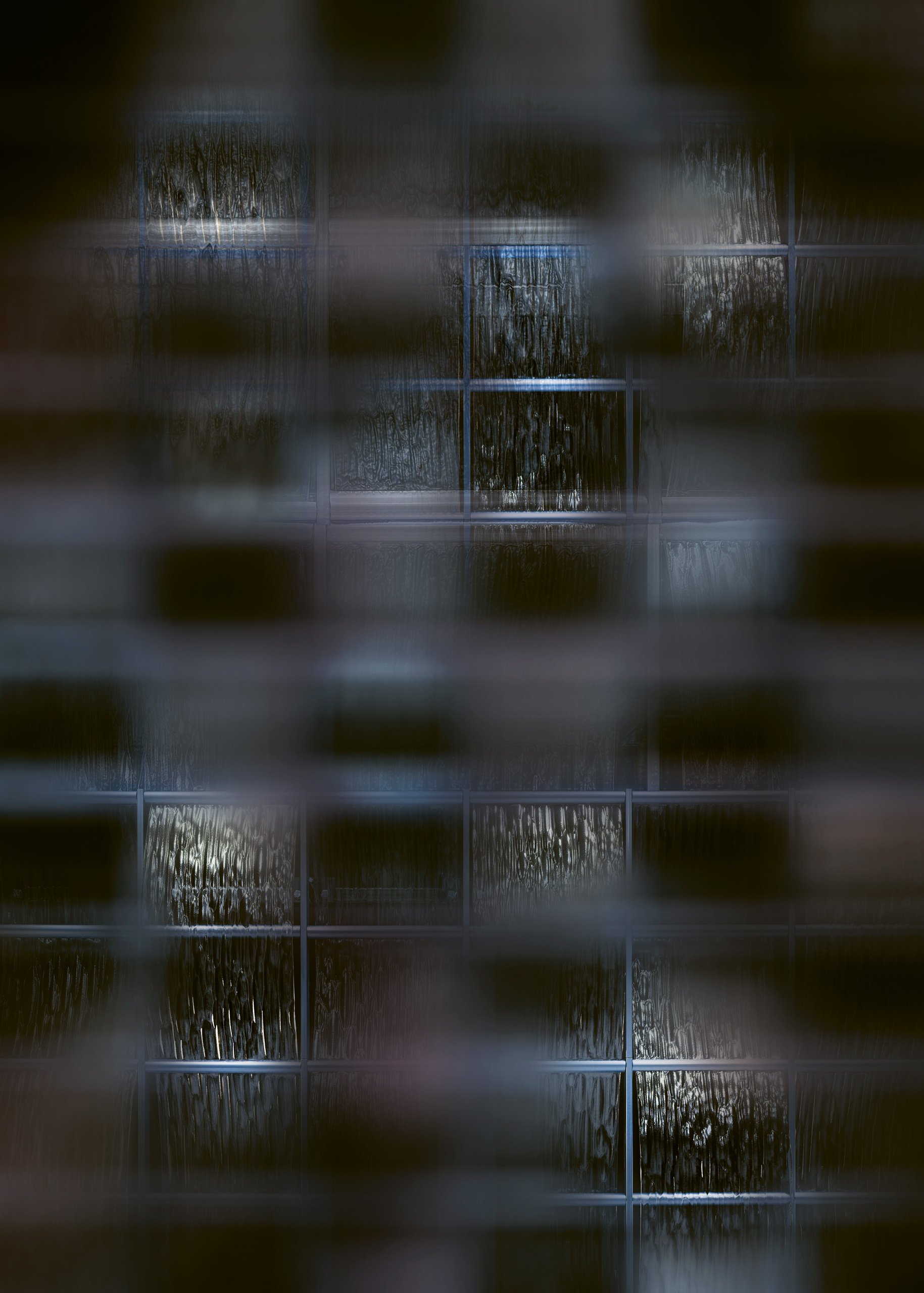

Decorative Art Walls combine modern technology and a classic architectural element used in various cultures. The design imitates the water surface and softly breaks down the background and identity of people. Can you find architect Daniel Libeskind behind one of the panels?

Maybe it would suffice to draw a protective circle with sacred chalk to create a private space. But a line is not a wall. Since the legendary story about the foundation of Rome, where after crossing the groove symbolising fortification of the city Romulus killed his brother Remus, it is clear that borders need to be respected. The motif of private fortification a fence was explored by the artist Kateřina Šedá in her project Furt dokola (Again and again) from 2008 and presented at the Berlin Biennale. The event involved a number of neighbours. With the help of various tools, they were trying to overcome replicas of fences that the artist built to look like their fences in Brno, which enabled taking down these monuments of privacy, at least for a little while.

For a long time, Martin Papcún has mapped the duality of the interiors and exteriors of the apartments in which he lived and creates objects of various scales – monumental and miniature – from the interspaces formed by the walls. The work, reminiscent of an architectural model called Buildings III (2013), is a silver object that can also be used as a brooch for its wearer.

What can be read as a truly monumental tribute to privacy are the concrete casts by the British artist Rachel Whiteread. As controversial and Brutalist form of mass, her work won the prestigious Turner prize in 1993. She managed to transfer the casts, often linked with fragile material like plaster, and the smooth bodies of classical sculptures into a different material, scale and the sphere of private home. Her sculptures create a stone tribute to entire houses, bathrooms and bed mattresses.

All design concepts of Lasvit Art Walls are modular either in terms of size, pattern, color-scheme, or intended interior use as partitions, or decorative walls.

As Semper underscored the historical meaning of textile as a primary material in the context of theory of architecture, it has remained a tool sought-after by many to create intimacy and a feeling of privacy. Drawn curtains in a window (inconceivable in the Protestant society) are a signal that something always stays hidden from outside onlookers. At the same time, curtains can become the final touch of the interior and create an inner comforting shell, much like in the instance of adapting the industrial powers of a former cement mill in Spain by Ricardo Bofill. Be it as curtains, carpets or tapestries, textile is making a comeback to interiors that were dominated by pure functionalism and cold minimalism for most of the 20th century.

How better to imagine the prenatal stage than in the form of an egg? The shell chair called Egg was designed by Arne Jacobsen in 1959 for a Copenhagen hotel. He was probably inspired by his 15-year-old Womb Chair, his Finnish colleague Eero Saarinen, who believed that we had never felt safe since leaving our mother‘s womb. In the 1960s, Eero Aarnio continued this hunt for a real sense of privacy with the Ball Chair.

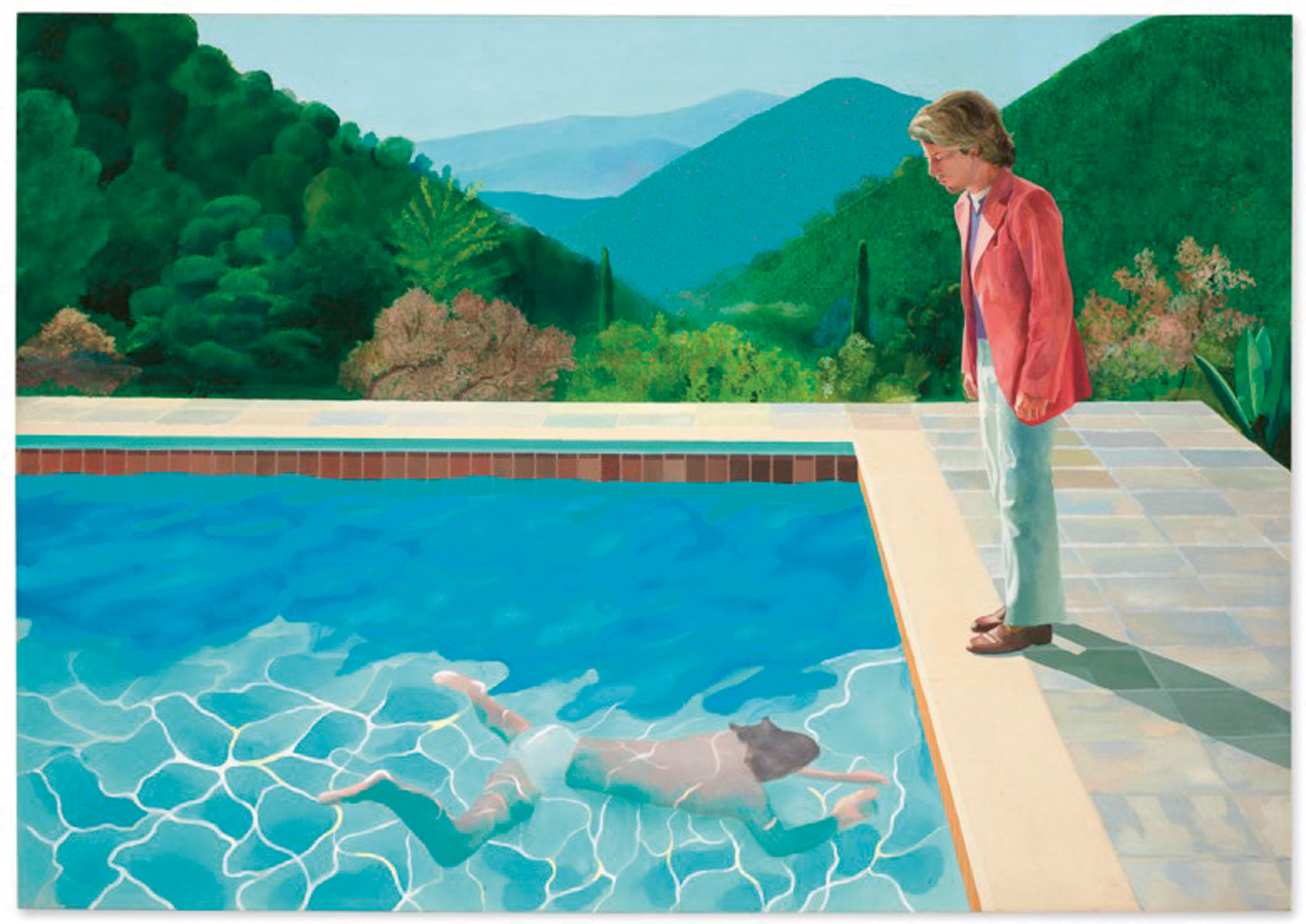

A bathroom and/or a pool is often considered the most intimate space of the house, where one moves completely naked. In both a pool and a bathtub, a person can become most powerless and vulnerable. Let us recall the series of Hockney’s images A Portrait of an Artist (1972) based on the iconic A Bigger Splash (1967). On the background of an idyllic Californian landscape and a luxurious modernist house we can see a swimmer under water observed by another man standing by the pool.

David Hockney‘s iconic painting Bigger Splash was preceded by a three-meter painting A Portrait of an Artist, which cryptically speaks of the relationship between the artist and his then partner. The monumental work opened a series dominated by private pools — nothing out of the ordinary in California, but very unusual for painters from cold England.

Where do we then experience the perfect feeling of privacy? Is it at all possible to experience this during our lifetime, after we leave the prenatal stage of an embryo in our mother’s womb? If we are seeking this feeling of ideal safety, warmth and embracement we will surely find a number of designer approaches that can replace the mother’s womb to some extent. There is the cosmic-futuristic modulated shell chair in the shape of an egg by the Scandinavian designers Eero Aarnio or Arne Jacobsen and also the new phenomenon of tiny houses – small self-sufficient houses located in abandoned areas and yet evoking the feeling of safety like the memories of our childhood hideaways. To a great extent, privacy also represents anonymity. In times of the pandemic the need to keep social distance and use only separated spaces plays into privacy’s hand. Yet we cannot forget the rather thin and dangerous line between privacy and isolation. So, where do you find the privacy of your dreams? Psst, that’s a secret.